10. Michelangelo and Sebastiano

National Gallery, London

This oddly conceived show set Michelangelo alongside his infinitely less interesting friend Sebastiano del Piombo and told the dullest story it could find from a life that was full of audacity and adventure. Yet it was all worth it for the sight of original sculptures by Michelangelo alongside some of his most stupendous drawings. His statue The Risen Christ was awe-inspiring.

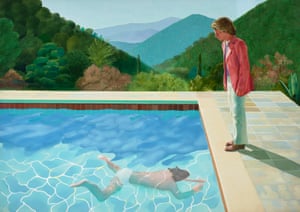

9. David Hockney

Tate Britain, London

The brilliance of Hockney’s paintings from the 1960s and 70s was gloriously reaffirmed by an exhibition offering one modern masterpiece after another. Most overwhelming of all was his 1972 painting Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures), the translucent turquoise water, melting landscape and silent psychological tension as a clothed figure watches a pale swimmer. But the genius on display in those early works made it hard to look at his later art, in which decline is so obvious.

8. Giacometti

Tate Modern, London

The tragic feeling and compassion of Giacometti’s later art, with its spindly specimens of an etiolated humanity bearing witness to the Holocaust, came as a body blow in this beautiful and epic presentation of one of the most profound artists of the 20th century. Yet it also did justice to his earlier participation in the surrealist movement with an unsettling array of his spiky, violent, erotic sculptures from the 1930s. His fascination with the ancient roots of art made this not so much a one-man show as a chunk of world history.

7. Mondrian

Gemeentemuseum, The Hague

Seeing how the great Dutch abstract artist evolved, slowly and thoughtfully, from painting rustic scenes to creating his own world of harmonious red, blue, yellow, black and white rectangles and lines was an eye-opener. The Gemeentemuseum has the world’s biggest collection of early Mondrians and it put them all on view, to show how deeply Mondrian was rooted in romantic landscape art. A visionary quest for inner truth.

6. Rachel Whiteread

Tate Britain, London

The power and poetry of Whiteread’s vision has barely changed since the early 1990s and doesn’t need to. In a simple, brilliant way she has overcome the emotional paralysis of minimalism by creating objects that are as objectlike as any arrangement by Donald Judd, yet bear traces of a ghostly past. The eerie beauty of these three-dimensional Victorian photographs of walls, stairs and the underneath of chairs invite reverie and dreams. A towering figure in today’s art.

- At Tate Britain, London, until 21 January.

5. Damien Hirst: Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable

Palazzo Grassi and Punta della Dogana, Venice

Fame and wealth cannot buy him universal respect. Like Dalí, he’s an artist whose merit will always be hotly debated: subversive imagination or kitsch nonsense? I suspect that, as with Dalí, critics will still be arguing that in 50 years. In other words, he will be remembered. This exhibition in Venice showed why: it outdid Jeff Koons or Andy Warhol in its embrace of pop culture, creating a museum that was a theme park, turning history itself into a hilarious rollercoaster.

4. Dalí/Duchamp

Royal Academy, London

The inspired madness of pairing these 20th century mavericks does wonders for them both. Dali’s depraved imagination and glossy painterly skill get the best possible staging, showing that he was a genuine original, even an erotic visionary, rather than just a kitsch poseur. Yet it is the genius of Duchamp that ultimately makes this unmissable. In the centenary year of his urinal readymade, the real riches of his mind are laid bare, with Dali as his loyal sidekick.

- At Royal Academy, London, until 3 January.

3. Portraying a Nation: Germany 1919-1933

Tate Liverpool

This was an unsettling mirror of our time, with many fearing we are returning to the age that produced Hitler with the rise of far-right politics and rampant populist rhetoric. Tate Liverpool opened a dark window on what the age of extremes looked like first time round. This absorbing history lesson compared two great witnesses of Weimar Germany: the anthropologically exact photographer August Sander, and the manically imaginative painter Otto Dix. While Dix’s paintings reveal the freedom and experimentation of urban Germany in the 1920s, the austere portraits of Sander show a much more conservative, constrained society, one that was waiting to take its revenge.

2. Raphael: The Drawings

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Much more intimate than his paintings, Raphael’s drawings were done solely by his own hand, whereas his frescoes had a team of helpers. This extraordinary exhibition did something very simple that worked brilliantly: it brought together these great drawings from the finest collections to give a moving view of how his genius grew. Drawings of massacres, disasters, motherhood and beauty – all rekindled my love of this artist.

1. Cézanne Portraits

National Portrait Gallery, London

Not many art exhibitions are truly important. They may be exciting, entertaining, absorbing – but when the dust settles and the posters are covered up with ads for the next unmissable show, nothing has really changed. This is one of the rare exceptions. Paul Cézanne, who died in 1906, has been iconic ever since Picasso and Braque picked up and turned his fraught, hard-won way of looking at apples, mountains and people into the broken mirror of cubism, yet his revolutionary importance is less well understood in the 21st century.

His portraits turn out to be the key that unlocks his genius for today. Even if his landscapes don’t punch their modernity into your mind, it really is impossible to ignore the strangeness and newness of the way he saw people. From early canvases (his portraits of his father and the painter Achille Empéraire, both sitting in the same high-backed chair, exuding a peculiar pathos) to a dazzling mature masterpiece (his boy in a red waistcoat posing, hand on hip, in diamond-faceted emulation of Donatello’s statue of David), this is an exhibition in which every single work is startling.

Cézanne rethinks and reinvents art before your eyes. Most profound of all are the self-portraits in which he wonders who he really is, gazing in ever-deepening anxiety at the remote face in the mirror. Ultimately it exposes how superficial our idea of innovation is, for Cézanne did not so much innovate as dig, hack and burn the fabric of perception itself. His one-man revolution was driven solely by an insatiable passion for truth that makes his portraits as authoritative as Rembrandt’s.

- At the National Portrait Gallery until 11 February